November 14, 1923 − March 25, 2011

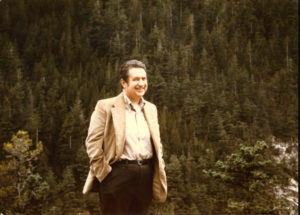

Born on November 14, 1923, in Rowley, Iowa, Gaustad grew up in Houston. After serving in the Army Air Corps in 1943−45, he graduated from Baylor University (1947) and completed his graduate work at Brown University (1951), where his mentor was historian Edmund Morgan. His teaching career took him from Shorter College in Rome, Georgia (1953−57), to the University of Redlands in California (1957−65) and finally to the University of California at Riverside. At Riverside, he organized an “education at home” program, open to students at any UC campus, that offered them a total immersion in colonial history at Williamsburg, Virginia. On retiring in 1989, he was named professor emeritus. He was visiting professor at Baylor University (1978), University of Richmond (1987), Princeton Seminary (1991−92), and Auburn University (1993).

A distinguished lecturer at other schools in the United States and abroad, he also served as President of the American Society of Church History and was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Speakers Panel. He received Distinguished Alumni Awards at both Baylor and Brown Universities, as well as the Distinguished Teaching Award at UC Riverside and the Alumni Religious Liberty Award from Baylor.

In 2002, Gaustad was an expert witness in the widely publicized trial brought by the ACLU, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, and other groups against Montgomery, Alabama, judge Roy Moore (Glassroth v. Moore), who refused to remove a monument of the Ten Commandments from the state courthouse. In his testimony for the plaintiff, Gaustad observed that Thomas Jefferson had “an undying anxiety of anything that would bring church and state together. He was not against religion. He was against any combination of power with religion.” When asked by Judge Myron Thompson if it would help to add a disclaimer to the bottom of the monument saying “We’re not compelling anyone to believe,” Gaustad replied that it would, but “moving it to private property would help more.” His expertise was also on display in the halls of Congress in 1995−96: in response to Representative Ernest Istook’s proposal of a Constitutional amendment allowing school prayer, Gaustad coined the slogan “Istook is mistook,” which soon found its way onto buttons worn by opponents of the amendment.

Upon the historian’s death on March 25, 2011, Martin E. Marty, professor emeritus at the University of Chicago, noted that “Edwin Scott Gaustad has been for decades the premier historian of religious dissent in the United States, a scholar who set his biographical subjects--Roger Williams, Benjamin Franklin, and others--into the context of the larger story well told in his pace-setting Religious History of America. He was also the atlas maker for two generations of Americans who wanted to fuse geographical and historical interests, as he himself did so well. His Faith of the Founders is much used in our time when it has become urgent to get an accurate reading on the story of religion in the national founding. He may have liked to tell the story of dissent, but one can only remember him as someone who gave assent to other scholars, audiences, and others who welcomed his generosity of spirit, and--to the end--his smile. Generations of students knew him not only as first-rate lecturer but also as a soul who will not soon be forgotten.”

And to author Jon Meacham, “Edwin Gaustad was one of America’s most important historians of religion and public life. With care, balance, and grace, he charted the tricky terrain of faith and politics, contributing immeasurably to our understanding of some of the most central questions confronting the nation. And he was a gracious scholar, always taking time to help others—which is the mark of a truly great man.”

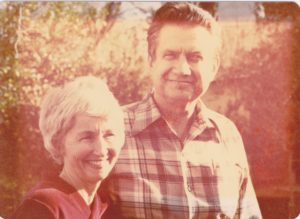

Gaustad’s kindness was legendary, and his family were the daily beneficiaries. He was married for sixty-three years to Helen Virginia Morgan (1926−2009), from Hillsboro, Texas, whom he met at Baylor. Their family to date includes three children (Susan, Scott, and Peggy), daughter-in-law Mimi, son-in-law Stuart, four grandchildren (Layna, Evan, Lili, and Sam) and spouses Dominic and Alicia, and three great-grandchildren (Oliver, Miles, and Bennett). Over the years, the family made welcoming homes in Providence, R.I.; Rome, Ga.; Redlands, Calif.; Easton Md (one year spent doing research at the Library of Congress); Anchor Bay, Calif.; and Santa Fe, N.M. Bookshelves could be found in all of them, holding treasured copies of (to take a random selection) Shakespeare, the Geneva Bible, The Brothers Karamazov, Ulysses, Thornton Wilder, Jon Hassler, Flannery O’Connor, Willa Cather, Robert Frost, T. S. Eliot, S. J. Perelman, The Letters of E. B. White, John le Carré, Reginald Hill, Robert Barnard, H. L. Mencken, Mark Twain, and the complete red-trimmed volumes of Ogden Nash. Possibly Nash (“Parsley / Is gharsely”) was the model for the Istook slogan. Most of his professional-related library as well as papers are now housed at Baylor, in the Scholars’ Collections / Gaustad Collection.

he met at Baylor. Their family to date includes three children (Susan, Scott, and Peggy), daughter-in-law Mimi, son-in-law Stuart, four grandchildren (Layna, Evan, Lili, and Sam) and spouses Dominic and Alicia, and three great-grandchildren (Oliver, Miles, and Bennett). Over the years, the family made welcoming homes in Providence, R.I.; Rome, Ga.; Redlands, Calif.; Easton Md (one year spent doing research at the Library of Congress); Anchor Bay, Calif.; and Santa Fe, N.M. Bookshelves could be found in all of them, holding treasured copies of (to take a random selection) Shakespeare, the Geneva Bible, The Brothers Karamazov, Ulysses, Thornton Wilder, Jon Hassler, Flannery O’Connor, Willa Cather, Robert Frost, T. S. Eliot, S. J. Perelman, The Letters of E. B. White, John le Carré, Reginald Hill, Robert Barnard, H. L. Mencken, Mark Twain, and the complete red-trimmed volumes of Ogden Nash. Possibly Nash (“Parsley / Is gharsely”) was the model for the Istook slogan. Most of his professional-related library as well as papers are now housed at Baylor, in the Scholars’ Collections / Gaustad Collection.

In Dissent in American Religion (1973)--which is dedicated to his three children “and to that unmoored student generation of which they were a part; together, they taught me more about dissent than I really wanted to know”--Gaustad wrote: “In the first century, amidst a plethora of fresh dissent, the sober counsel was ‘Test everything; hold fast what is good.’ It is sober counsel for every century, and every generation. Dissent neither conducts the examination nor controls the results; it only insures throughout history that testing will take place.” And from his biography of Thomas Jefferson: “The book of Samuel speaks of those who are ‘bound in the bundle of the living.’ Americans need to be so bound together, bound by sentiment and hope, by values and civility--bound by something more than a network of interstate highways.”

Edwin S. Gaustad: A Remembrance by Leigh Eric Schmidt

His obituary as published in the New York Times